Procrastination is a universal human experience, often dismissed as a simple lack of discipline or poor time management. However, research consistently shows that procrastination is rooted in complex emotional processes, closely tied to stress, mental fatigue, self-esteem, and our broader sense of well-being and longevity. Understanding these connections is crucial for effective stress management and optimizing performance and energy in daily life.

The Emotional Mechanics of Procrastination

At its core, procrastination is not just about avoiding work—it’s about avoiding difficult emotions. When faced with tasks that trigger anxiety, fear of failure, boredom, or self-doubt, people often delay action to escape these uncomfortable feelings. This avoidance offers temporary emotional relief, activating the brain’s reward system and providing a fleeting boost in mood. Unfortunately, this short-term gain comes at a long-term cost: as deadlines loom, stress and anxiety intensify, creating a vicious cycle of avoidance and emotional distress.

Stress: Both Cause and Consequence

Procrastination and stress are locked in a reciprocal relationship. Stressful contexts—whether due to external pressures or internal emotional turmoil—deplete our coping resources and make us more vulnerable to procrastination. When overwhelmed, the brain’s ability to regulate emotions and maintain self-control diminishes, increasing the likelihood of delay. Conversely, the act of procrastinating generates further stress, as unfinished tasks accumulate and the pressure to perform mounts.

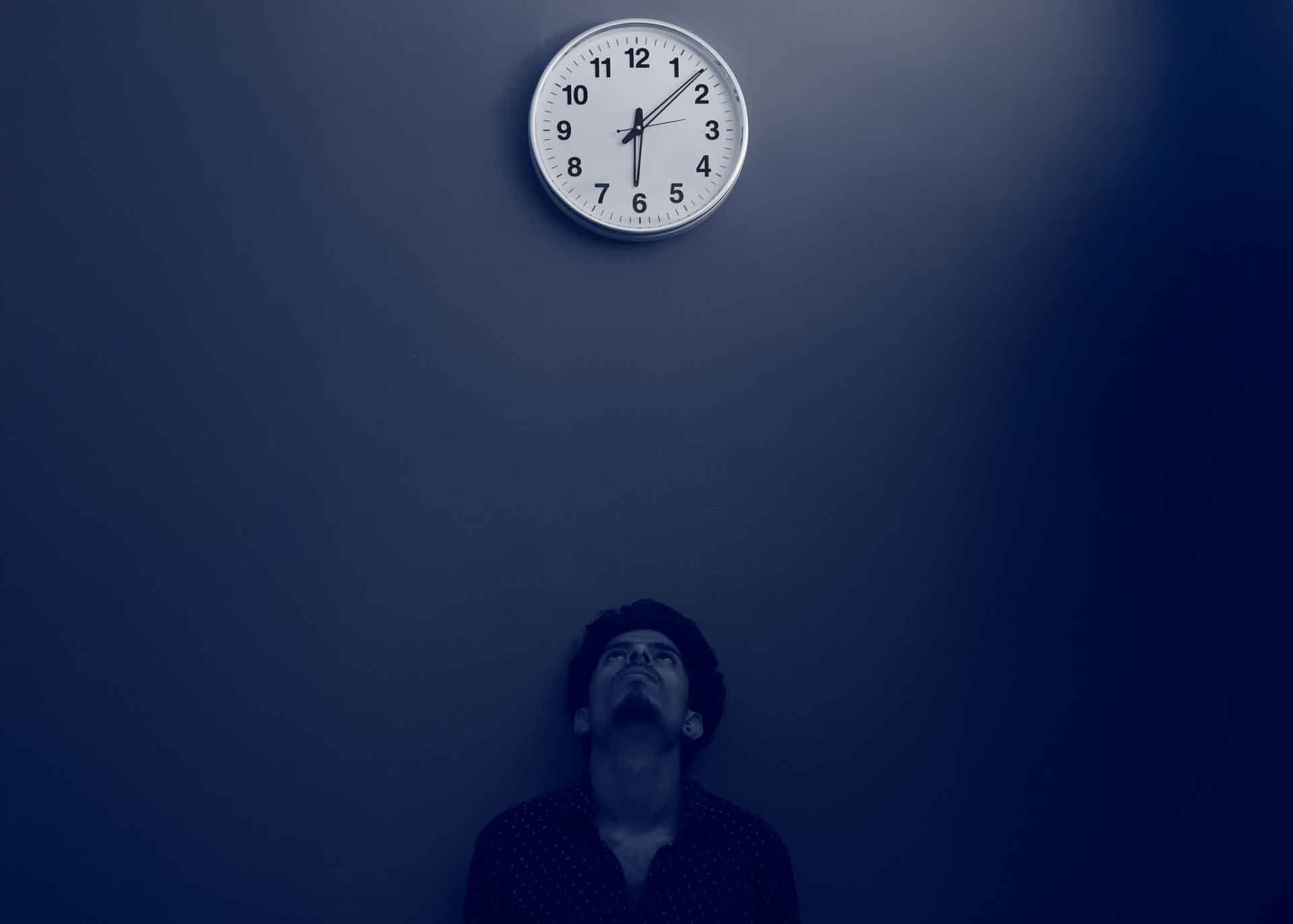

This dynamic is particularly evident in high-pressure environments, such as academic or professional settings, where performance expectations are high and the consequences of failure are significant. Here, procrastination can undermine not only productivity but also mental health, leading to chronic stress, poor sleep, and even physical health issues over time.

Mental Fatigue and Energy Depletion

Mental fatigue plays a significant role in procrastination. As cognitive resources are drained by decision-making, concentration, and emotional regulation throughout the day, self-control weakens. This depletion makes it harder to resist distractions and stay focused on challenging tasks, especially when energy levels are low. The result is a greater tendency to seek instant gratification and avoid effortful activities, further perpetuating procrastination and reducing overall performance and energy.

Self-Esteem and Self-Compassion: The Inner Dialogue

Low self-esteem is both a cause and a consequence of procrastination. Individuals with low self-esteem often doubt their abilities and fear negative evaluation, making them more likely to delay tasks to avoid potential failure or criticism. Over time, repeated procrastination can erode self-confidence and life satisfaction, creating a downward spiral that affects not only academic or work performance but also general well-being and longevity.

Self-compassion emerges as a crucial buffer in this process. Studies show that people who are kinder to themselves in the face of setbacks are less likely to experience the debilitating stress and negative self-judgment that fuel procrastination. Cultivating self-compassion can promote adaptive coping strategies, reduce the emotional burden of delay, and support better stress management and resilience.

The Impact on Performance and Longevity

Chronic procrastination undermines performance by creating a cycle of last-minute rushes, increased errors, and missed opportunities for learning and growth. The constant stress associated with this cycle can also have long-term health implications, contributing to mental fatigue, burnout, and even reduced longevity due to the cumulative effects of chronic stress on the body.

Breaking the Cycle: Strategies for Stress Management

To combat procrastination, it is essential to address the underlying emotional drivers:

- Stress Management: Mindfulness, relaxation techniques, and regular physical activity can help lower baseline stress and improve emotional regulation.

- Boosting Self-Esteem: Setting realistic goals, celebrating small achievements, and reframing negative self-talk can enhance self-confidence and motivation.

- Managing Mental Fatigue: Prioritizing rest, breaking tasks into manageable steps, and minimizing decision overload can preserve cognitive energy and self-control.

- Cultivating Self-Compassion: Practicing kindness toward oneself during setbacks reduces negative emotions and supports adaptive coping.

Conclusion

Procrastination is not a simple flaw in character or willpower—it is a complex emotional response to stress, mental fatigue, and self-doubt. By understanding and addressing these underlying factors, individuals can improve their energy, performance, and overall well-being, ultimately supporting greater satisfaction and longevity in both personal and professional life.

If you want to learn more on how to deal with procrastination, book your free longevity assessment call